There’s a story that goes like this. A man comes across three men laying bricks. He pauses to watch them and then walks over to the first man. “What are you doing?” he asks. The first bricklayer shrugs and says, “I’m making $15 an hour.” The man then moves on to the second bricklayer and asks the same question. The second bricklayer glances up and says, “I’m building a wall.” The man approaches the third bricklayer and again asks, “What are you doing?” The third bricklayer stands straight up and proudly points to the heavens. “I’m building a cathedral,” he proclaims. The moral of the story is that a brick is just a brick until it is brought into a grander context and vision. It’s the same way with the transformation of information into knowledge.

Intelligence has a hierarchy. At its base is data — cold hard facts and figures easily derived from a search on Google or Bing. Data is excellent at answering trivia questions but its usefulness ends there. It’s the equivalent of the bricklayer’s $15 an hour response. When data is aggregated it can be viewed in context and, at that point, becomes useful information — similar to the concept of “building a wall.” Like bricks, the data points supplement and complement each other and create a more complete picture. But — and this is an important but — information has to be synthesized and internalized in order to become true knowledge. That process of synthesizing and internalizing represents thinking — putting together “data bricks” and creating something far greater and more valuable than the sum of the parts.

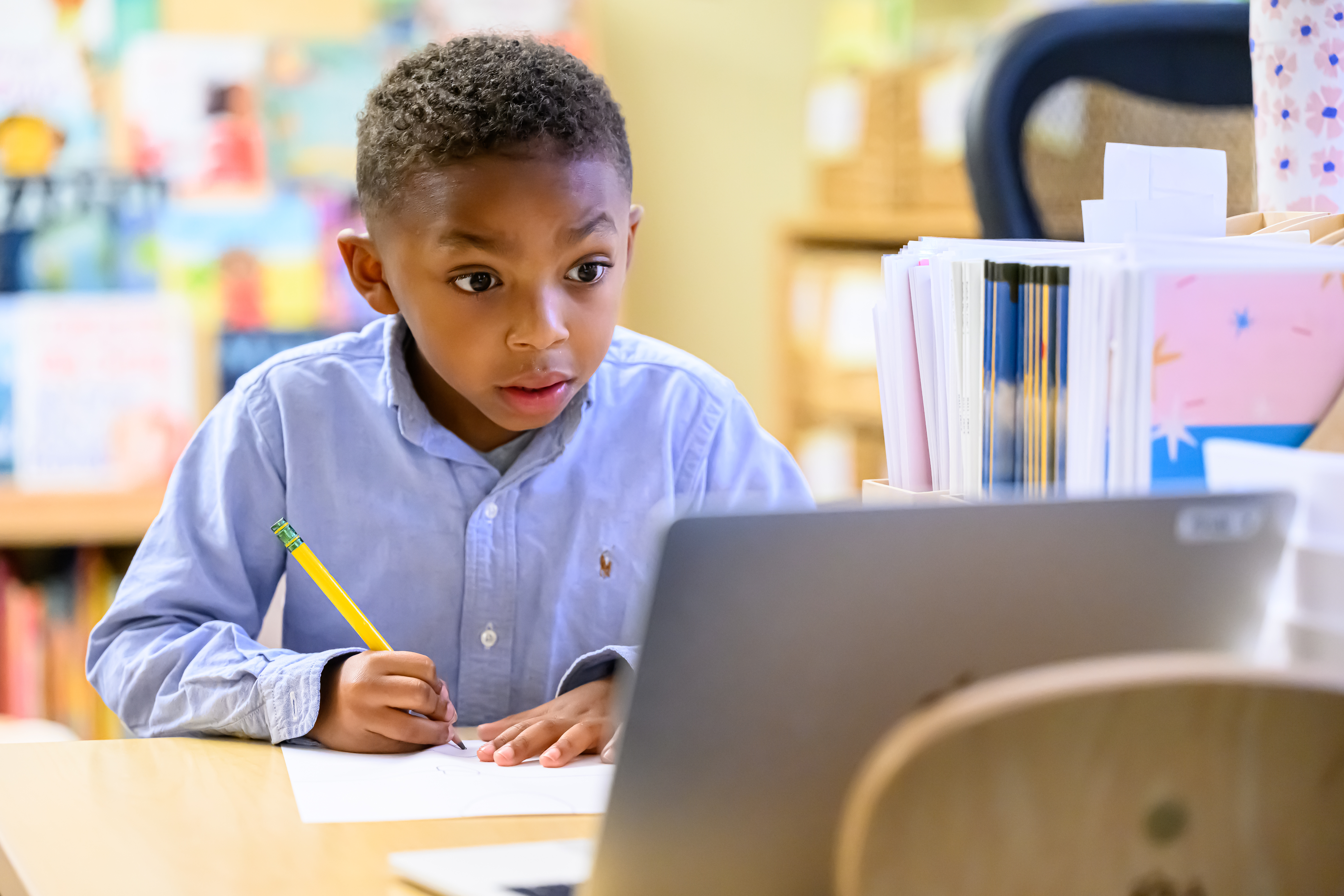

The Importance of Education Beyond Online Searches

The ability to think, and the transformation of information into meaningful knowledge, is the Holy Grail of education. As a result, a key responsibility of today’s schools is to teach children — starting at the earliest grades — how to think. Achieving that goal has become more difficult in the Digital Age. While few would suggest that technology has been a detriment to society, it seems clear that the increased use of digital resources has put an increased focus on information rather than thinking. In MIT’s Rethinking Learning in the Digital Age, author Mitchel Resnick states, “Teachers cannot simply pour information into the heads of learners; rather, learning is an active process in which people construct new understandings of the world around them through active exploration, experimentation, discussion, and reflection. In short: people don’t get ideas; they make them.”

The critical word in Resnick’s statement is ideas. Information is to ideas what bricks are to a cathedral. Information is a building block; ideas are the result of the human mind’s virtually unlimited ability to craft wonder from fundamentals. Ideas do not come from Google inquiries, Facebook posts, or Instagram images. The catalyst for ideas may come from those sources but the creation of a breakthrough idea/insight/innovation comes from the individual. And not just any individual — individuals who have been taught to think at a young age.

Moving Past Screens

In today’s digital age, it’s easy to get caught up in online searches and videos when learning. However, there’s more to education than just what you can find online.

An independent school education provides a holistic experience that goes beyond academics, fostering personal growth, social skills, and emotional intelligence. The boarding program at Fessenden also emphasizes the well-being of students, ensuring they develop into well-rounded individuals ready to face the challenges of the future.

How to Incorporate Data Without Relying on It

Every school and every parent wants their students and children to succeed academically, grow socially, and enjoy every possible advantage. Every school and parent, however, has a different approach to achieving those goals. Many of those approaches are decidedly “old school” — think flashcards — and are information-centric rather than thought-engendering. Going back to Resnick’s quote, these approaches pour data over young children with the hope that some of it gets absorbed. The problem is that even if the data is absorbed, it’s just data. Discrete and unconnected data bytes.

Rather than flooding students with data, many schools today are allowing students to be more “entrepreneurial” in how they learn. Allowing them to be more active and independent in the classroom. Working in small groups on hands-on projects that cross disciplines so they can learn from each other, from observing, and from doing. And as they experience the depth of interconnected learning, students will realize that the information gleaned from a Google search is not an end unto itself. It is merely a beginning.

See How Fessenden Does School Different

At Fessenden, we believe in fostering curiosity and critical thinking, guiding students to ask the right questions and discover answers through hands-on learning and meaningful exploration, not just by looking up the right answer.

Are you ready to help your child develop the skills to think deeper and achieve more? Schedule a tour or Contact us today to learn how Fessenden’s approach to education can make a lifelong difference.

Read On

If My Son Goes to an All-Boys Elementary, Will He Be Awkward Around Girls?

3 Reasons to Enroll Your Son in an All-Boys Kindergarten.